By M.K. Swartsfager, Staff Writer

For many young veterans like the Marine reservists I serve with, November is an especially busy and emotionally complicated month, especially since the Marine Corps Birthday is celebrated on November 10, just one day before Veterans Day. November calls for a reconciliation of our experiences with the continuing reality of war and the people who wage it. After all, Veterans Day was originally called “Armistice Day” to celebrate the end of World War I; the supposed “War to End All War”.[1] To some, Veterans Day is about more than mattress sales. It should be an inescapable public call for solemnity, in recognition of service and sacrifice.

In observance of Veterans Day, the legal profession should renew conversation on the reasons to recruit, advance and retain veterans in the bench and bar. Admittedly, the task is a little self-serving, as I am on the hunt for an employer. However, I have noticed in some of my interviews that the tone of the conversation abruptly changes when we discuss the military portion of my resume. I want to go on the record and reject any notion that gratitude for service is a valid reason to distinguish veterans from other applicants, associates, or employees. Instead, I encourage leaders in the legal field to look for three qualities in the experiences of veterans that are of conspicuous value to our profession.

First, many veterans are practiced in the performance art of national security, a transferable skill to litigation and leadership more broadly. Military drill, customs and courtesies are a constant instruction in bearing, tact, and respect when engaging in an exercise of trust. Even further, wars of the past century have illustrated the importance of communicating effectively with leaders and the public, controlling the narrative to achieve strategic objectives. Some veterans have taken that lesson to heart. As trained performers, many veterans understand how storytelling and individual behavior can communicate the competencies that build or break down trust.

Second, veterans tend to have honed skills for thinking tactically, operationally, and strategically. The notion that the U.S. military turns volunteers into mindless, order-following automatons is an inaccurate stereotype. Quite conversely, the professional military education that is ubiquitous across services and ranks emphasizes the importance of high-quality decentralized decision-making. Many veterans have a well-tested sense of judgment, and a bias toward confident decision-making hewn by experiences in many different ethical environments. The diversity of tactical and operational experiences veterans provide can improve the quality of work product and offer increasingly creative solutions for leaders to consider.

Finally, and most importantly, military volunteers demonstrate a commitment to service and a willingness to pursue public objectives, even at personal expense. As public servants, veterans are aware of how hard it is to serve in the public trust. Historically, Congress and the public demand that the military achieve critical objectives and enable diplomatic success while operating within tight ethical and legal boundaries. Indeed, the social tasks and ethical demands placed on the military often prove nearly insurmountable, if not patently impossible. However, that problem isn’t exclusive to the military; in fact, it is a reality shared by those who practice law.

It’s no secret that the legal profession sometimes suffers from poor public perception. An unfair but common duality holds that lawyers are either sclerotic rule-followers whose only pleasure is schadenfreude, or professional scofflaws who earn a handsome fee by justifying injustice. It’s easy to imagine the frustrated corporate boss saying, “run this past legal, but make sure they don’t see you.” Likewise, the ever-present and sometimes noxiously silly advertisements for lawyers ensure the idea of an “ambulance-chaser” sticks in the national imagination.

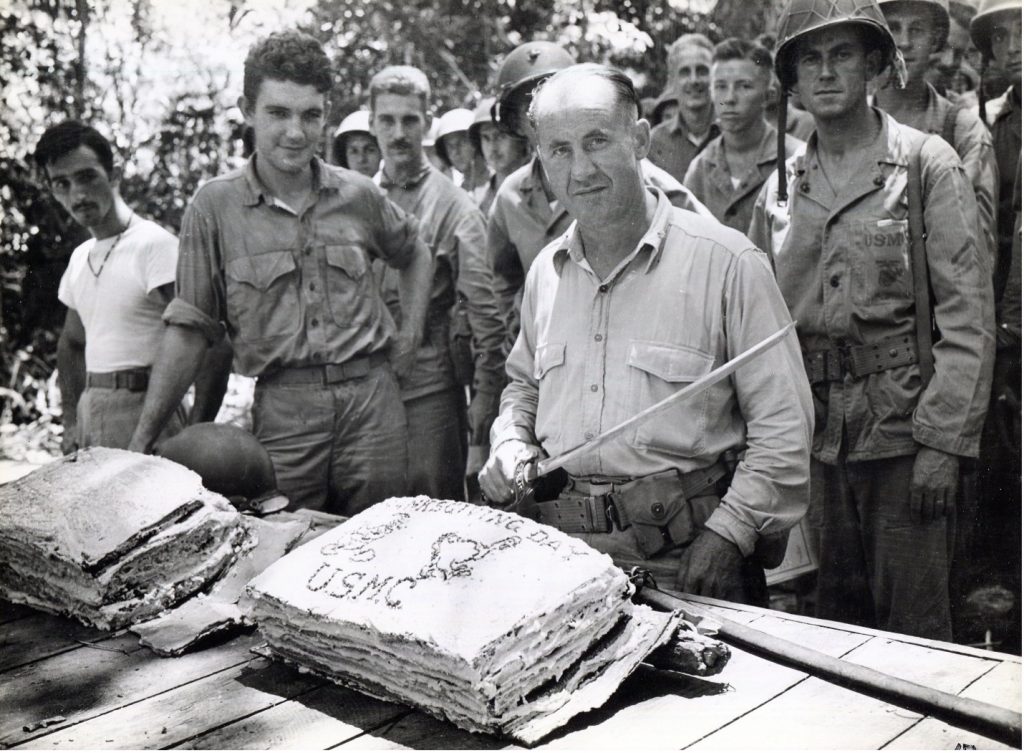

Add to those perceptions the litany of real issues presented by our laws. Add to that the substantial difficulty in creating just and fair outcomes in an enormous, diverse and powerful nation such as ours. It quickly becomes understandable that lawyers and the public sometimes lose sight of our constitutionally professed belief in the rule of law. We sometimes forget that the law’s potential to arbitrate conflict, reduce violence and forge lasting peace without domination is nothing short of sacred. Ultimately, we should take time to remember that the profession at arms and the profession at law descend from a common ancestor, and together derive from universal social demands for security, conflict resolution, and justice. Peace relies on “sacrifice,” which literally means “the doing of something sacred.” Few understand that reality the way that veterans do.

[1] https://department.va.gov/veterans-day/history-of-veterans-day/.