By Jennifer Carter, Feature Editor

If you are unfamiliar with blockchain technology and will be practicing law in the next five years, you should educate yourself yesterday. This groundbreaking development in technology has the potential to revolutionize the way attorneys approach contracts and transactions. The technology provides an unchangeable record of chain of ownership that can be viewed by any permitted user and includes evidence of any manipulation of the records of the item in question. The beauty of this technology is that while the chain is visible to users, past “links” in the chain cannot be manipulated; therefore, the record cannot be hidden, deleted, or changed in anyway. This lends transparency to everything from financial transactions, to prior contract drafts, to proper property titles.

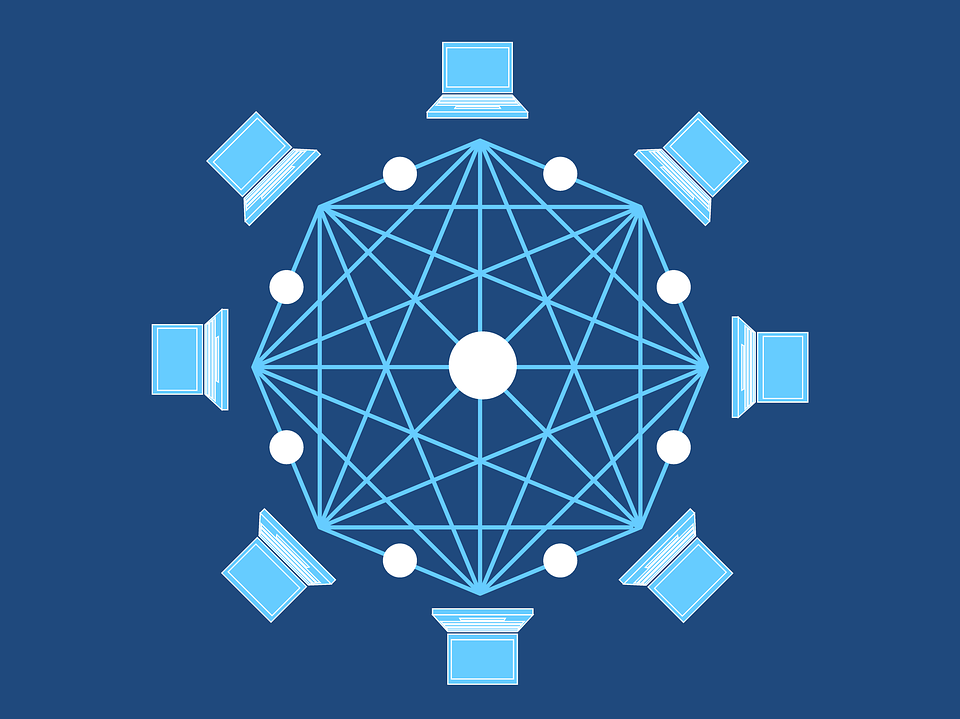

This educational demand begs a brief explanation of what blockchains are and how they work. Assistance is found in Blockgeeks’ boiled down definition, that provides, “A blockchain is . . . a time-stamped series of immutable record[s] of data that is managed by cluster of computers not owned by a single entity. Each of these blocks of data (i.e. block) are secured and bound to each other using cryptographic principles (i.e. chain).”[1]

Let’s break that down a little further. A “block” is a data file that is encrypted so that the data cannot be manipulated.[2] The block acts as a “ledger” and describes: action taken upon a document, the details of a financial transaction, or the transfer or a deed or other instrument.[3] The block contains information such as a timestamp, and it notes any actions that were taken.[4] The block also contains a connection to the previous block in the chain, called a “hash.” [5] Because each block is linked to the one before and the one after, the chain cannot be broken or manipulated.[6]

The “immutable record of data” refers to the inability of each block in the chain to be manipulated. Because a block is encrypted once it is created, the data contained in the block and the hash linking the previous block cannot be hacked or edited by a user because to do so would change the entire series of blocks and destroy the chain. Instead, any edit or change appears as an additional block in the chain, rather than an edit to an earlier block. Liken this to the growth of a tree. Once you cut into the trunk, the rings contain evidence from throughout the life of the tree and any manipulations or effects suffered by the tree. The rings in the trunk act as a ledger for the life of the tree. This is how blockchains work on documents and transactions, all the while saving the timestamp, information of the editor, and keeping the edits in order chronologically, yet still producing a legible end-product with the most up-to-date changes visible.

Additionally, because the data in the blockchain is not managed by a single entity, the ability for any blocks to be secretly manipulated is decreased to near impossibility. Imagine data that is saved in a cloud that is accessible to more than one user. Because many users may add to a single blockchain via this “peer-to-peer” system, the chain is rendered unchangeable.[7] Jimi S. of Good Audience demonstrates this process as applied to Bitcoin, stating, “[m]illions of users are mining on the Bitcoin blockchain, and therefore it can be assumed that a single bad actor or entity on the network will never have more computational power than the rest of the network combined, meaning the network will never accept any changes on the blockchain, making the blockchain immutable.”[8] Because the blockchains are decentralized and openly accessible, bad faith manipulation is nearly impossible. The consequence in the legal field is trustworthy documents and transactional records along with transparency of previous transactions, making this technology is ideal for numerous legal uses such as contract negotiation, property ownership records, and financial transactions.

To give an illustration to the intersection of blockchain and law, I will use the example of a property transaction. First, the property firm will need a blockchain developer. A cursory search for one on Indeed.com provided over five hundred results in my area.[9] Once a developer has created a genesis block (origination block) for the piece of property, the transaction can begin.

Next, a buyer expresses interest in the property. They can receive access to the original block of data to inspect the property’s specifications and title details. Once the buyer decides to move forward, a transaction will occur which will be recorded in subsequent blocks attached chronologically to the original (genesis)[10] block. Thus, a small chain has begun to form. When the buyer is ready to sell to a subsequent buyer, the same process will occur, creating more blocks and a lengthier chain. However, this subsequent buyer can inspect the genesis block and the transactional data that occurred between the original firm and the original buyer to ensure transferability, value, and specifications.

If this technology is applied to such a property over the course of decades, the property may change hands numerous times. The blockchain becomes increasingly valuable to guarantee rights to the property and ensure that specifications are not lost or changed by errors in writing or unrecorded interests. And because the blockchain is encrypted, the users with access to the chain can allow or restrict other users from viewing the data.

The financial world has already seen use of this technology in the decentralized cryptocurrency Bitcoin.[11] Financial firms can glean from Bitcoin the benefits that Blockchain affords, including streamlined communication between financial institutions and legal departments regarding transactions and verified records of previous transactions.

The uses for blockchains are apparent for financial transactions, smart contracts, cryptocurrency, and property transfers.[12] Recently, supply chains have emerged as a benefited user of blockchains.[13] Apparel supply chains are using the technology to provide transparency in their manufacturing process to ensure that creation of products remain sustainable and responsible.[14] Additionally, demand for blockchains for the sale and resale of luxury goods will likely explode.[15] Because the internet is replete with counterfeit luxury items, blockchains will ensure that a consumer is getting what they pay for.

Blockchain technology has not emerged without criticism.[16] Deloitte pointed out that blockchain suffers from slow transactional speeds, a lack of interoperability among developers, the high cost and complexity of developing and operating blockchains, a lack of legislative regulation, and few firms on board with current use of the technology.[17] These hurdles, however, are due to the technology’s infancy, and Deloitte points out that each issue is being met with applicable solutions that will only take a matter of time to surmount.[18]

If you have not already experienced a demand for blockchain use in a legal setting, it is likely that you will see it emerge within the next few years. Lawyers in many fields will likely begin to use blockchains in contracts, financial transactions, property and wealth transfers, and document editing. Understanding how blockchain technology works and can be used is a first step in keeping with the technological advancements in the legal field.

Sources

[1] What is Blockchain Technology? A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners, Blockgeeks (Mar. 1, 2019),

https://blockgeeks.com/guides/what-is-blockchain-technology/.

[2] Block (Bitcoin Block), Investopedia (Jul. 5, 2018), https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/block-bitcoin-block.asp (last visited March 31, 2019).

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Jimi S, How Does Blockchain Work in 7 Steps — A Clear and Simple Explanation, Good Audience Blog (May 6, 2018), https://blog.goodaudience.com/blockchain-for-beginners-what-is-blockchain-519db8c6677a.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] https://www.indeed.com/q-Blockchain-Developer-jobs.html (follow “blockchain developer” search results) (last visited Mar. 31, 2019).

[10] Glossary, Bitcoin, https://bitcoin.org/en/glossary/genesis-block (Last visited Mar. 31, 2019).

[11] Olga Kharik and Matthew Leising, Bitcoin and Blockchain, Bloomberg (Nov. 2, 2012 2:51 PM EDT)

https://www.bloomberg.com/quicktake/bitcoins.

[12] Wikipedia, Blockchain, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blockchain#Blocks (last visited April 19, 2019)

[13] Samantha Radocchia, Altering the Apparel Industry: How The Blockchain Is Changing Fashion, Forbes (Jun. 27, 2018 6:55 PM) https://www.forbes.com/sites/samantharadocchia/2018/06/27/altering-the-apparel-industry-how-the-blockchain-is-changing-fashion/#49b3b7c329fb.

[14] Id.

[15] Jeffrey H. Greene and Anne Marie Longobucco, What is Blockchain and What Can it Do for the Fashion Industry?, The Fashion Law (Apr. 24, 2018), http://www.thefashionlaw.com/home/what-is-blockchain-and-what-can-it-do-for-the-fashion-industry.

[16] Ryan Browne, Five things that must happen for blockchain to see widespread adoption, according to Deloitte, CNBC (Oct. 1, 2018 8:57 AM EDT), https://www.cnbc.com/2018/10/01/five-crucial-challenges-for-blockchain-to-overcome-deloitte.html.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.