by: Lauren Gailey, Associate Editor

On January 24, 2013, Nevada Attorney General Catherine Cortez Masto announced that she is reconsidering her office’s arguments against same-sex marriage in a case currently before the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit “are likely no longer tenable.” Masto, a Democrat, felt compelled to do so after the Ninth Circuit issued another decision that read United States v. Windsor, the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court ruling striking down DOMA, as requiring courts to apply heightened scrutiny to government classifications based on sexual orientation.

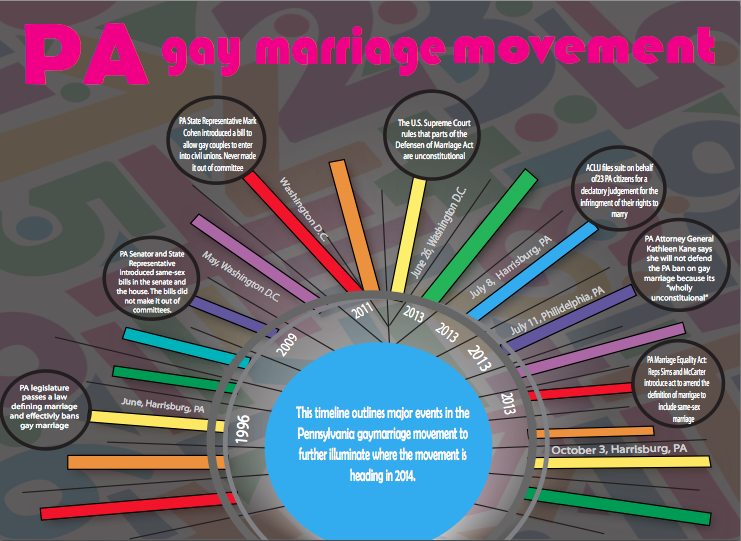

While Masto based her decision on controlling precedent, officials in other states have offered a number of different reasons for reevaluating their offices’ positions on same-sex marriage. Two other Democrats, Pennsylvania Attorney General Kathleen Kane and newly elected Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring, have both announced that they view their states’ bans as unconstitutional and will not defend them in court. Herring and Montgomery County, Pennsylvania Orphans’ Court Clerk D. Bruce Hanes, who was barred in September by the Commonwealth Court from issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, also expressed a desire to stay, in Hanes’ words, “on the right side of history.”

This emerging trend of elected officials interpreting and enforcing the law according to their own consciences and legal analyses has the potential to create great confusion among courts and citizens alike as to what the law is. In 2013’s Hollingsworth v. Perry, which involved a challenge to California’s Proposition 8, the Supreme Court did not reach the constitutional issue because California officials’ decision not to defend the referendum led the Court to order the case to be dismissed on standing grounds. Windsor narrowly escaped the same fate. In fact, much of the criticism of the Court’s decision in Windsor has centered on the Court’s willingness to find that a group of legislators (as distinguished from the private party in Hollingsworth) had standing to defend DOMA in lieu of the Obama administration, which declined to do so.

Even worse than muddying the legal waters for the courts, executive branch officials’ decisions can have real consequences for the people who rely on them. Hanes issued marriage licenses to at least 32 same-sex couples in the summer of 2013—32 couples whose marital status was thrown into question after the Commonwealth Court barred Hanes from issuing more licenses. Because marital status affects important legal issues like taxation and the inheritance of property, it is vital that public officials do their best to prevent citizens from relying on rights that they do not actually have under state law as it presently stands.

More obviously, elected officials like Kane and Herring take oaths that require them to uphold the laws of their jurisdictions. Presumably, this duty refers to the laws as they are currently written, not as they are interpreted by a single official or administrative office. No matter how well-intended a public official’s actions may be, enforcing the law according to one’s own conscience is simply not the duty with which he or she is charged—nor is it the duty the taxpayers pay their elected officials to carry out.

An Attorney General’s refusal to enforce laws in court is most troubling in that it undermines the very structure of the government itself. As any sixth-grader who has taken a social studies class knows, the legislative branch makes the laws, the executive branch enforces the laws, and the judicial branch interprets the laws. When an executive branch official takes on additional interpretive duties and declines to enforce the law, power is allocated unevenly and the system of checks and balances among the three branches is compromised.

Even supporters of same-sex marriage, who cheered the actions of Kane and Herring as victories, might be wise to greet the trend toward Attorneys General refusing to defend laws in court with caution. When so much discretion is afforded to the individuals who occupy public offices that they can alter the balance of the government itself, the tide could just as easily reverse itself if opponents of same-sex marriage take power.

It was for this reason that John Adams, in his role as a drafter of the Massachusetts Constitution in 1780, famously enshrined his commitment to “a government of laws, and not of men” into its text. In examining the current trend of Attorneys General and other officials declining to defend duly enacted laws on the basis of their personal beliefs, legal analyses or political motives, citizens must consider to what degree they are willing to support a “government of men.”

This was the second post of a two-part series. You can find the first post HERE.

Lauren Gailey follows the Supreme Court beat for Juris Blog and also currently serves as an Executive Articles Editor of the Duquesne Law Review. Her scholarly writing has focused on such diverse topics as the Fourth-Amendment constitutionality of GPS trackers and airport body scanners, amending the Federal Rules of Evidence to protect doctors who apologize to their patients, the complex relationship between the U.S. Supreme Court and the state high courts, and the divergent views of the U.S. and French systems toward the wearing of religious clothing in schools. Now in her final semester of law school, she hopes to explore many other interesting legal issues before earning her J.D.