By Samantha Cook, Feature Editor

When asked to write a post on the topic of a conflict nation, I started to think about the nature of conflict.

We typically think of war as an armed conflict between countries’ governments over some geographical, economic, political, or religious dispute. When that dispute is resolved, and when one head of state surrenders, the other country wins. Hitler committed suicide in a bunker, Truman dropped bombs in Japan, and WWII was over.

But when we think about the “nations” against which the U.S. has been engaged in conflict over the last several decades, it becomes challenging to understand the dispute at the core of the conflict, and even more challenging to understand who can decide when the conflict is over.

Students of high school civics and constitutional law know that Congress has the sole power to declare war.[1] Any American who has been alive for the past 17 years knows that the military has been engaged in an ongoing War on Terror all over the world. But perhaps fewer Americans know that the last time Congress formally declared war was in 1942, during World War II.[2]

A simple logical syllogism would suggest that all of the military conflicts following WWII have been unconstitutional: if Congress hasn’t been declaring war, then who has?

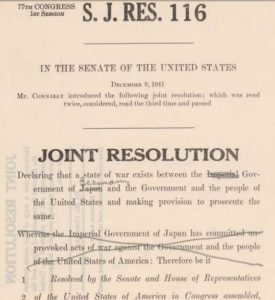

The reality is that the method of “declaring war,” a term with a disputed Constitutional meaning,[3] has become as equivocal as war-making itself. A formal declaration of war – like the one against Germany in 1941 – identifies a foreign country’s government as an enemy, authorizes the President to use military force, and pledges “all the resources of the country” towards defeating the clearly-defined enemy until the conflict is resolved.[4]

Since the 1940’s, enemies have become less clear, military technology has become more sophisticated and lethal, and the conflicts at hand have no reasonable resolution. The formal declaration of war was phased out and replaced with a somewhat more self-explanatory type of resolution: the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF). In the immediate wake of 9/11, Congress, scrambling to identify the attackers and understand their motives, passed a joint resolution authorizing force against those responsible.[5] This law is the Constitutional basis for what became known as the War on Terror. Contrast the scope of the 1941 declaration of war against Germany with that of the 2001 AUMF:

“… to carry on war against the Government of Germany…”[6]

“…to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons…”[7]

This seemingly boundless authorization, coupled with President George W. Bush’s rhetoric in a Joint Session of Congress where he stated that the War on Terror would not have a “decisive liberation of territory and a swift conclusion”[8] (as the Gulf War did), put the American people on notice that the War on Terror would be a new kind of warfare.

The AUMF has been the legal basis for numerous conflicts against countless enemies over thousands of miles of geographic territory. Most notably, the U.S. has been engaged in the War in Afghanistan, aiming to dismantle the Taliban and prevent it from harboring terrorist groups. Also pursuant to the 2001 AUMF, the U.S. involved itself in civil wars in Iraq, Somalia, Yemen, Syria, Libya, and Pakistan by aiding pro-government forces against Islamic militant insurgent groups. Now, almost 17 years after the 2001 AUMF – $2 trillion and tens of thousands of lives later – there is still no “swift conclusion” in sight.[9]

An AUMF carries the same weight as a declaration of war in that it provides Congressional authorization to engage in wartime activities. One of the most notable legal interpretations of the AUMF was in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, in which the Supreme Court ruled that the U.S. military could detain an American citizen residing in Afghanistan who was allegedly a member of the Taliban. The AUMF was written with broad language to authorize the use of force against “nations, organizations, [and] persons” associated with the 9/11 attacks, with no special protection for American citizens.[10]

We can all agree that Congress has to authorize military force, right? It’s plain and simple, not only in the Constitution, but in the War Powers Act, too. Under the War Powers Act, the President can only use force when attacked or when authorized by Congress.[11]

It seems clear-cut enough… well, maybe not in practice.

The U.S. has been fighting on the ground against Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) for years, but technically, ISIL was formed after the 9/11 attacks.[12] On two occasions, President Trump authorized operations in Syria against the Assad regime, which was not involved in the 9/11 attacks at all. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis defended these actions and stated that “the president has the authority under Article II of the Constitution to use military force overseas to defend important U.S. national interests.”[13] Secretary Mattis seems to have forgotten to add, “pursuant to Congressional authorization.” Obama administration interventions in Libya, though supported by NATO, were similarly shaky in their legal justification.

Two senators are now addressing the elephant in the room. Senators Bob Corker (R-TN) and Tim Kaine (D-VA) are proposing a new AUMF that would entirely repeal the existing legislation from 2001.[14] To briefly summarize the proposed changes, the Corker-Kaine bill:

- Narrows the conflict to a set of named stateless terror groups and associated forces, which the President can modify within 30 days of the resolution passing

- Specifically bars the President from targeting a sovereign state for harboring a terror group

- Requires the President to report to Congress within 48 hours of using force in a “new foreign country,” or a country other than Iraq, Syria, Somalia, Yemen, or Libya

- Authorizes the President to continue to use force until Congress passes a bill restricting that power[15]

The last bullet seems to flip the War Powers Act on its head. Doesn’t the President need to ask Congress for authorization every time he uses force unless the U.S. is attacked? The Corker-Kaine bill has a long road ahead and will most likely face its fair share of political and constitutional battles, but it’s the first semblance of a remedy to what has become an arguably lawless decade of armed conflict.

Sources:

[1] U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 11.

[2] https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/history/h_multi_sections_and_teasers/WarDeclarationsbyCongress.htm

[3] UNLEASHING THE DOGS OF WAR: WHAT THE CONSTITUTION MEANS BY “DECLARE WAR”, 93 Cornell L. Rev. 45

[4] https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/SJRES119_WWII_Germany.pdf

[5] https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-107publ40/pdf/PLAW-107publ40.pdf

[6] https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/image/SJRes119_WWII_Germany.htm

[7] 107 P.L. 40, 115 Stat. 224

[8] https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2001/09/20010920-8.html

[9] https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/war-afghanistan-numbers-n794626

[10] Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507, 124 S. Ct. 2633 (2004).

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_Powers_Resolution

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_State_of_Iraq_and_the_Levant#Foundation_(1999%E2%80%932006)

[13] https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Releases/News-Release-View/Article/1493610/statement-by-secretary-james-n-mattis-on-syria/

[14] https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/DAV18476.pdf

[15] Id.